This guest post written by Ellie Carpenter appears as part of our theme week on Unpopular Opinions.

When Nathan Rabin wrote at The A.V. Club about Elizabethtown in 2007, he likely didn’t anticipate that four of the review’s 799 words would be the subject of apology seven years later. The disparaging label given to Kirsten Dunst’s character Claire and Natalie Portman’s Sam in Garden State — Manic Pixie Dream Girl — referred to the emerging trend of women characters in film who exist “solely […] to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” His succinct identification of the trope didn’t inspire audiences to be critical so much as it inspired imitation.

After films such as Garden State and Elizabethtown, Manic Pixie Dream Girls (MPDGs) seemed ubiquitous. Free-spiritedness and quirky girlish charm manifested repeatedly on-screen throughout the mid-2000s and 2010s. In this time, the MPDG label was applied liberally to nearly any female character who might fit in the parameters even tangentially. Mainstream and feminist critics alike used it to indict female characters as poorly-written, misogynist, and shallow, but few questioned whether the supposed failings of the MPDGs may actually be the fault of the male leads in these films.

The criticism most commonly leveraged against MPDGs — and that which Rabin initially referred to — is that their only apparent purpose is being in service towards the male lead. A viewer who can only see this in a character such as Garden State’s Sam, though, has perhaps adopted the shortcomings of the film’s other lead. Out of context, Sam is an imperfect yet realized character. She lies, dances strangely, has epilepsy, and works as a paralegal. Some of these traits may now seem cliché, but they exist as part of Sam’s character whether or not she has an audience.

It is another of her traits, however, which has perhaps invited so much criticism. When his friends propose watching porn and doing coke, Andrew objects and says that Sam has already been corrupted enough. “I’m not innocent,” she responds, but Andrew insists: “Yes, you are. And that’s what I like about you.” He becomes angry until Sam seemingly begins to mock him: “He was protecting me. He likes me. You’re my knight in shining armor!”

Andrew sees only her whimsy, charm, and a host of other obvious projections. That he fetishizes these traits is no fault of her own, and to dismiss her character is to do the same. This pattern, though, is the one established by most of the characters who fell prey to the MPDG label. Much like Sam, Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s Ramona Flowers in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World was maligned as a shallow object of Scott’s fantasies. Overlooked, however, are her bisexual identity, job working for Amazon, and apparent ability to travel through dreams.

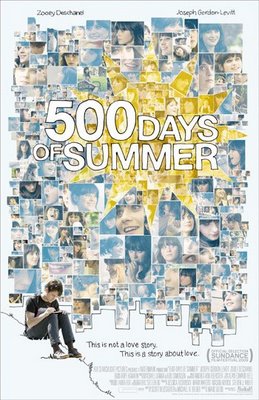

If Claire, Sam, or Ramona were paired with a male lead who saw them as full people rather than objects to derive inspiration from (and fuck), perhaps the MPDG label never would’ve happened. It is typical, though, that the women in these films be blamed for the projections and fetishization they are subject to from their male counterparts. This is never illustrated better than in the film that might have ended Manic Pixie Dream Girls once and for all: 500 Days of Summer. Zooey Deschanel’s Summer is the subject of infatuation for Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Tom, but his objectification is revealed in retrospect after the relationship ends. Her initial appearance as little more than a cliché is the result of his immaturity rather than any character flaw on her part.

Manic Pixie Dream Girls aren’t problematic because they’re quirky and girly; that audiences only see them as such is often indicative of shitty male leads who are intent on making women fit into their fantasies. Perhaps we adopt these tendencies while watching films too, and maybe it is better male characters we should be lobbying for: ones who see women as autonomous beings and treat them as such. Many critics have now recognized the overuse of the MPDG label, but it was the originator of the term who touched on an enduringly problematic part of the trope.

In his 2014 apology, Rabin made clear what should have always been known: the Manic Pixie Dream Girl phrase was intended to identify misogynist trends in film rather than perpetuate them. He also shifted focus to the male characters in these films who had previously managed to largely escape critique. He identifies them as “miserable” and “mopey, sad white men” who rely on the cheeriness of a flighty muse to overcome their ennui.

Examining Manic Pixie Dream Girls reveals a group of characters with diverse interests, ambitions and stories, but unfortunately, that’s where the diversity stops. Rabin merely mentions whiteness as a hallmark of the trope, but it is this trait which is the most troubling. If there is a single attribute that all MPDGs model as an ideal, it is the obligatory whiteness that they all have in common. He specifically names “white men,” but the unanimous whiteness of the women in these films, too, suggests that to be white is a prerequisite for the relationships depicted.

One of the lesser known bearers of the MPDG label, Emily Browning’s character Eve in God Help the Girl, is the subject of Sarah Sahim’s Pitchfork essay The Unbearable Whiteness of Indie. She articulates what persists as a problem in indie film, music, and culture: “White is the norm,” and the “movie serves as a microcosmic view of what is wrought by racial exclusivity.” Indeed, Eve’s character succeeds in rejecting conventions of the MPDG trope by maintaining her autonomy and resisting the objectification of her would-be partner. Like Summer did, however, she also illustrates the presence of a much bigger problem. The casting call indicates producers are “open to Eve’s nationality” yet goes on to restrict it to British, French, or Australian (and there are plenty of people of color in these nations).

An unpopular opinion though it may be, MPDGs are not and have never been a major problem in film — at least not for the reasons typically cited. They sure are a great distraction from other issues, though! Instead of critiquing whether or not our idealized white characters are complex or empowering enough, perhaps we should turn our attention to advocating for the inclusion of more diverse casts and people of color, not to mention LGBTQ people and people with disabilities, in the films we watch. Manic Pixie Dream Girls haven’t been cool since 2012 anyways.

See also at Bitch Flicks:

Elizabethtown After the Manic Pixie Dream Girl

Women Empowerment and LGBT Issues in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Movie Review: 500 Days of Summer, Take 1

(95) Minutes of Pure Torture: 500 Days of Summer, Take 2

Take Away This Lonely Man: 500 Days of Summer and Musical Storytelling

God Help the Girl: Sunny Glasgow Hosts a Twee Musical

Ellie Carpenter is a writer and graduate student from California currently living in Nashville. After barely surviving two years in Portland, she decided to move to the deep south, but don’t read too far into it. Areas of interest include relationships, feminism, sex work, pop culture, music criticism, and celebrity. Commentary on all of the above can occasionally be found on Twitter @ersatzelevator.